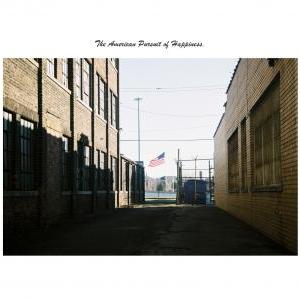

As the slogan goes, ‘Detroit Hustles Harder’. Once the third-largest city in the United States, now Detroit is so synonymous with economic collapse and architectural ruin that the images of its decay are as clichéd as they are poignant. As the home of the US auto industry’s ‘Big Three’ – Ford, Chrysler and General Motors – Motor City relies on federal life-support, and with a population that has contracted by more than 60 per cent since 1950, Detroit has enough vacant land to accommodate Manhattan, Boston and San Francisco combined.

If ‘America is the original version of modernity’, as Jean Baudrillard believed, then Detroit offers us a vision of what the end of modernity might look like.

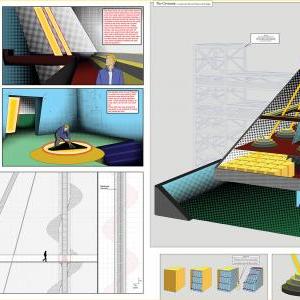

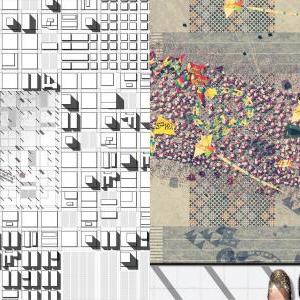

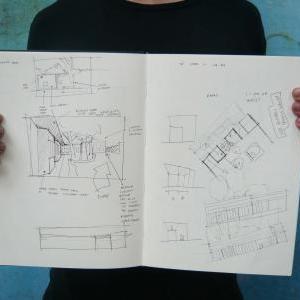

This year Intermediate 1 visited Detroit to confront the idea of architectural redundancy. Acting as archaeologists of the immediate future (to paraphrase Reyner Banham), our considerations uncovered misplaced artefacts, failed architectural precedents and images of past declines and future ambitions. Working in defiance of conventional architectural norms, the unit sought to design real, surreal or entirely speculative interventions within the remains of the Paris of the West.

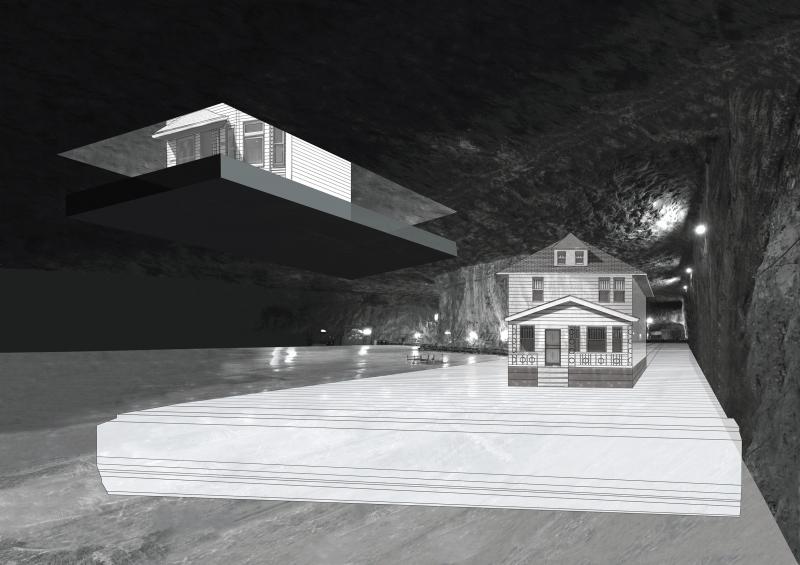

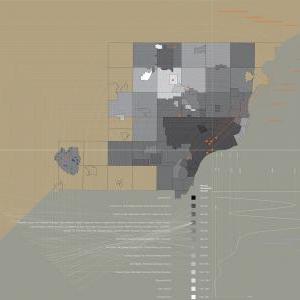

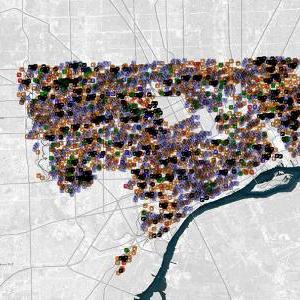

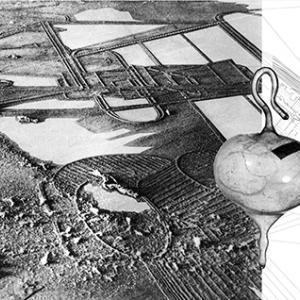

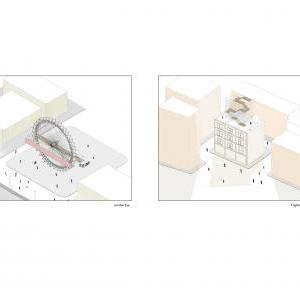

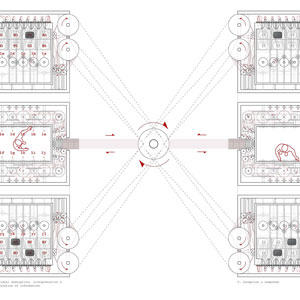

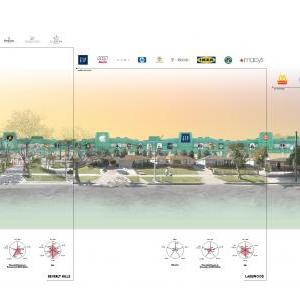

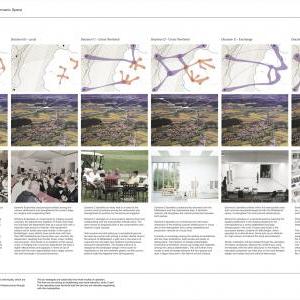

Projects included providing a religiously inspired exodus to Michigan’s Upper Peninsula; detoxifying the city by sealing residents in the Packard Plant; stripping a suburb of all historically consonant detail; refunding citizens by allowing them to rework their houses using neighbouring buildings; redefining Gratiot Avenue through the last remaining corner store; adjusting the relative density between the suburbs and downtown through demolition; using the urban prairie to farm road-kill; restarting the Packard assembly line to disassemble the surrounding workers’ accommodation; relocating the banks along Woodward Avenue to the local police station; delivering mail by tank; allowing the most avaricious developers to fight it out; and, finally, creating a ‘living archive’ of the city housed in a reclaimed salt mine beneath East Detroit.

Staff

Mark Campbell

Stewart Dodd

With thanks

Barbara-Ann Campbell-Lange

Kate Davies

David Dunster

Belinda Flaherty

Kenneth Fraser

Murray Fraser

Thomas Haywood

Jerry Herron

Francesca Hughes

Saskia Lewis

CJ Lim

Claire McManus

Monia Di Marchi

Joel Newman

Frank Owen

Christopher Pierce

Tom Powell

Charles Rice

Damian Rogan

Constantino di Sambuy

Ingrid Schroeder

Marc Schwartz

Takero Shimazaki

Brett Steele

Sylvie Taher

Vere Van Gool

Manja Van der Worp

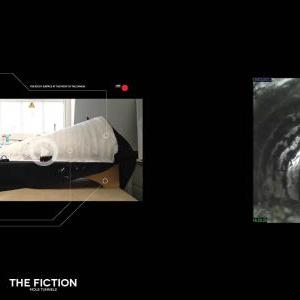

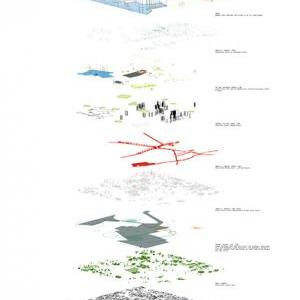

Lara Daoud

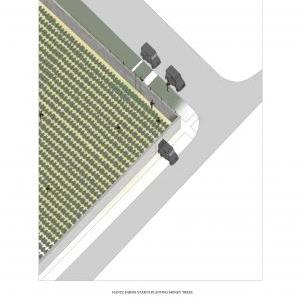

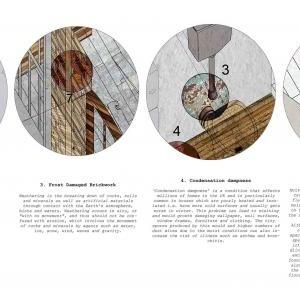

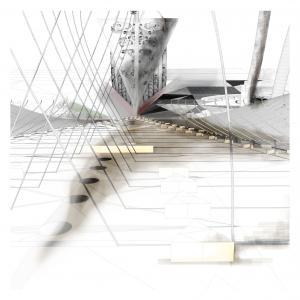

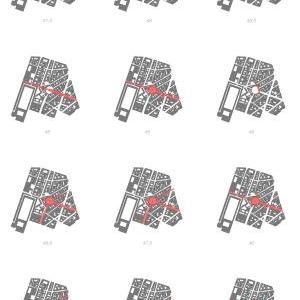

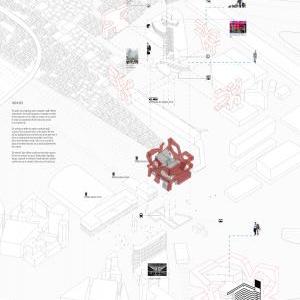

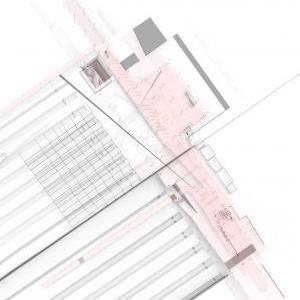

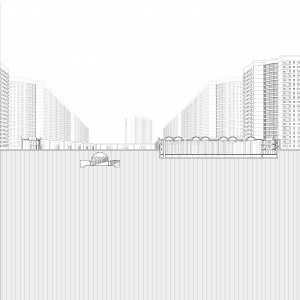

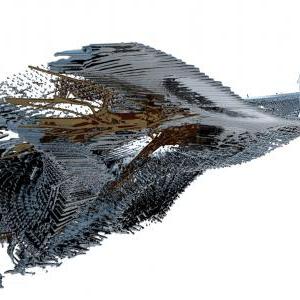

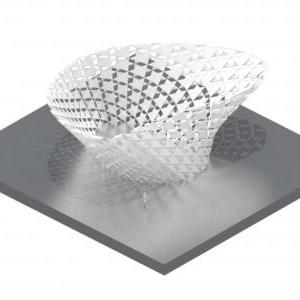

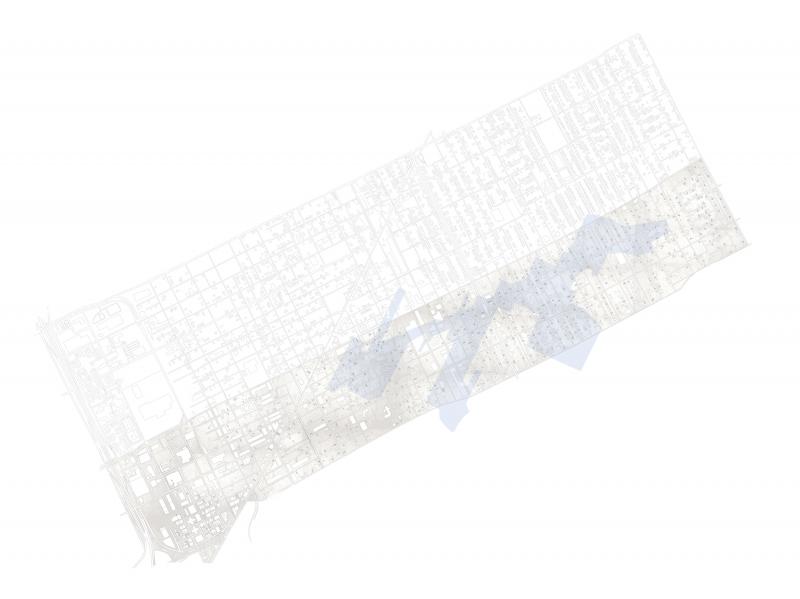

East Detroit comprises mostly of timber neighbourhoods, whose houses are sitting ducks susceptible to arson attacks. Having visited the Detroit Fire Department, I became curious about these attacks and how the city addresses the issue. The fire department categorises arson under 4 categories; 1. arson for profit 2. arson for revenge 3. pyromaniac arson 4. Juvenile arson. There is even a period called 'Devil's Night' around Halloween where pyromaniacs rampantly burn vacant houses. Since the Detroit fire department has laid off a lot of its fire fighters, the few that remain are overburdened, given that Detroit has one of the highest arson rates in the country. Since they can't see to all the fires, they have adopted a 'let it burn' policy where if the house stands in isolation and is known to be unoccupied, it is left to burn. Often however, there is the danger of a snowball effect where the fire can raze a whole neighbourhood at a time if the houses stand within close proximity to each other, which they often do. The Detroit Fire Department predicts that over the next 100 years, a bounded area in East Detroit, which I have chosen as my site, will be razed by fire over the next 100 years. In my other research, I discovered that the Detroit salt mine lies beneath this area in the East. It has been abandoned for the most part and is currently owned by the 'Detroit Salt Company' who still operate in a very small percentage of the mine. Articles I read dating back to the 40s described it as one of the biggest salt mines in the world, lined with 80 miles of road, with ample artificial lighting. Vehicles have been abandoned in its tunnels. The juxtaposition of the fragile timber neighbourhoods above ground and this robust, indestructible structure that lies below ground is something that resonated in my mind. I thought of staging an intervention over the 100 years, to ensure the preservation of an East Detroit neighbourhood. There is only one neighbourhood which remains intact within my chosen site and I thought that it could be sacrificed, along with its inhabitants and reconstituted in the salt tunnels 400 ft below ground. It could become an inhabitable archive and the existing miners' transport to ground level could still be used, which emerges behind Eastern Market. This is the only old brick building which stands on this site and it could provide the inhabitants with a food supply and life support. Eventually, the inhabitants of the sacrificed neighbourhood will die off, and it will become a time capsule. The idea is to preserve a fragment of East Detroit for the generation to come. In order to fund this act, I thought that the Detroit Salt Company could expand its operations, with a high demand for road salt in the region. In the winter months, the salt is needed to de-ice all the motorways in Michigan, particularly the motorways in Detroit, that were a result of the booming auto industry in the 30s. I am proposing the Detroit Salt Company as the client in this project, to effectuate this act of preservation and sustain its upkeep, regulating visits to the archive.

![[ I-2 ] The Role of the Community](http://pr2013.aaschool.ac.uk/submission/uploaded_files/INTER-01/thumbnails300/Steven.Price-1.jpg)

to tunnel level. This is the existing vertical transport that the miners used..jpg)