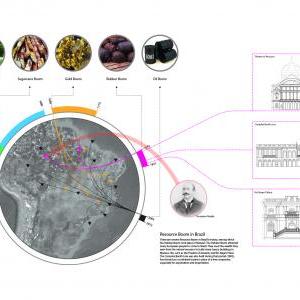

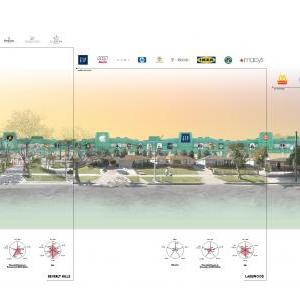

Six hours and 30 minutes upriver from Manaus, the capital of the Brazilian state Amazonas, we reach our destination: a once-glamorous town, now abandoned and infested by fire ants. The only inhabitant is a Japanese man. Soap opera blasts from a TV in his hut as he explains how one should unfold a hammock to avoid the ants. At 10pm the power generator shuts off, leaving only darkness and the progressive myth of the Amazon – a populated forest connected by drones and long-distance technology that lives as a dream-resource reservoir for the dream of preservation itself.

In the morning our expedition into this technological environment continues. Moments of an Indian shaman wearing a sleeveless Panasonic t-shirt intertwine alongside tourist-friendly swimming with dolphins and a gigantic river filled with trash. The notion of natural resources and how gate-cities operate is renewed by Manaus’ dedication to religious processions and its belief in Santa as a valued asset.

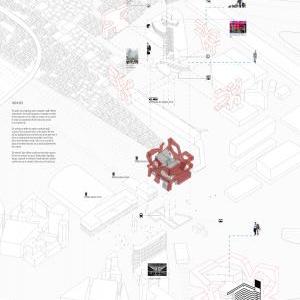

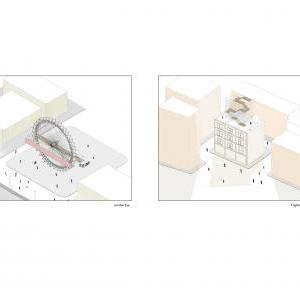

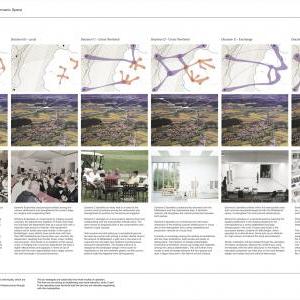

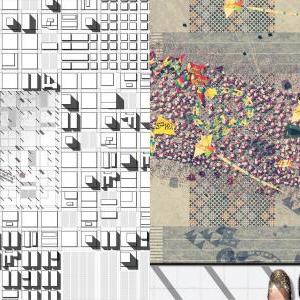

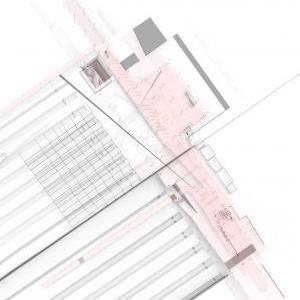

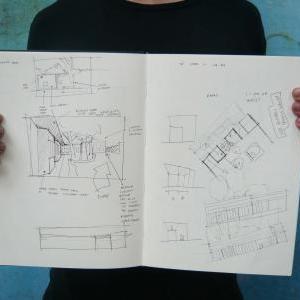

Inspired by a non-linear view of reality in shamanism and an increase in ADHD patients, Shahaf Blumer designs a clinic in Manaus whose space addresses the notion of psychedelic as a form of treatment. As an alchemist and mad scientist Stefan Jovanovic recreates the call of rain and floods in the Amazon basin. Utilising people as participants he generates a sonic environment that reverberates in the slow burn of an instrumental totem. Alvaro Fernandez fever dreams of beaming the Amazon Theatre broadcast to his ‘Digital Operas of the Amazon’ at the Royal Geographical Society in London. In a desolate ant-infested city northeast of Manaus, Gordon Gn Guanlian designs a blood bank outpost that operates as a node-giving lifeline to humans in need of transfusions.

What is a resource? If the alchemical world operated as proto-science in its confusing clash of obscurantism and truth, would preservation be a proto-environmental phase? A transition stage? A moment of shift? If so, it is necessary to re-search for what the bricks and mortar of this transformational world could become.

Unit Staff

Nannette Jackowski

Ricardo de Ostos

Thanks to our visiting critics

Manuel Jiménez García

Apostolos Despotidis

Chryssanthi Perpatidou

Giles Bruce

Javier Castañón

Mollie Claypool

Oliver Domeisen

Laura Barbi

Kasper Ax

Marianne Mueller

Gian Luca Amadei

Abel Maciel

Roberto Bottazzi

Nate Kolbe

Charles Walker

Alice Labourel

Yael Reisner

CJ Lim

Tyen Masten

Ellie Stathaki

Alex Kaiser

Stefan Jovanovic

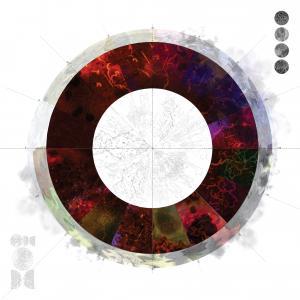

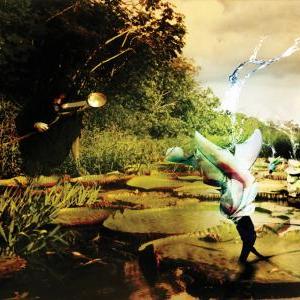

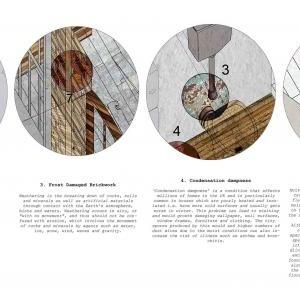

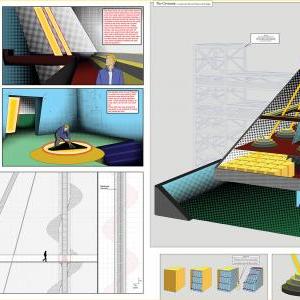

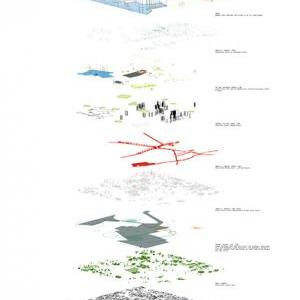

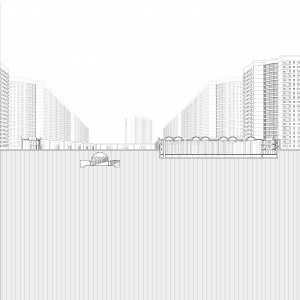

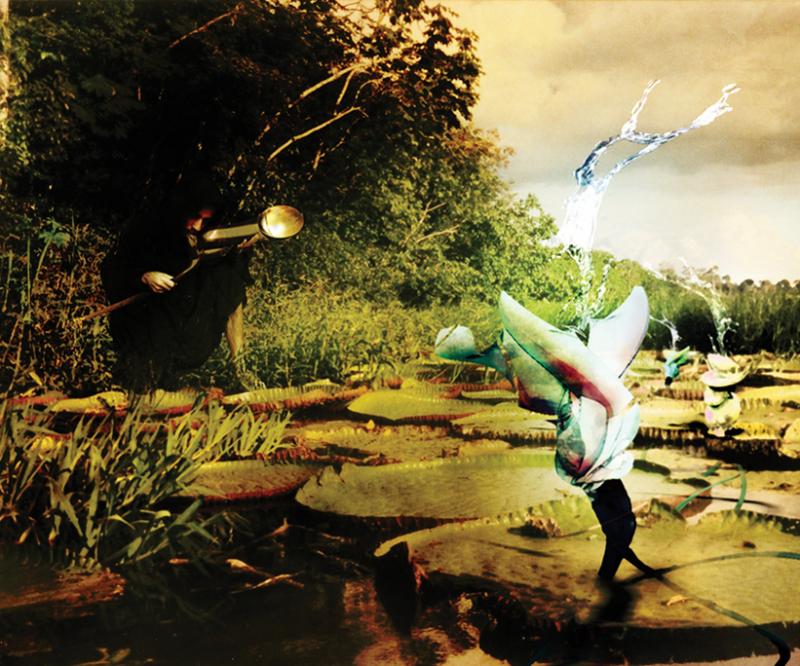

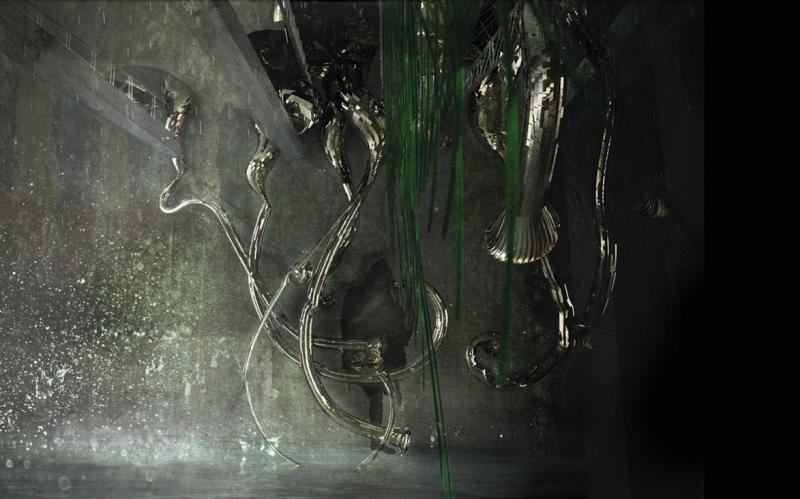

Where the rivers meet, music is heard. Where the Rio Negro and Rio Solimões converge, the church tower bells can be heard; chiming away as the waters begin to rise. The sky meets the land, and water becomes the only medium between heaven and earth. In the cataclysm of the rising river and the down pouring rain, the calling of the far forest roars…and somewhere in the distance the shaman blows his horn. The lilies would dance, and choreographies of water would blossom from the quiet riverside. But, these are all fleeting moments of a storyteller’s imagination, memories and re-memories of a magical reality.

It is known that the temple, half submerged, half floating, above the Rio Negro’s surface was the home to he who would signal the beginning of the flood season. The skies would pour down, and the river would come to life. It is a regenerating cycle, like the Ouroboros, flushing out the old, and bringing life to a redefined ecosystem.

While the rain season reaches its peak between the months of February and May, the sun would hide behind the clouds, and let the moon take the center stage. It is when the shadow sun is full, that the rains would reach their highest and most explosive momentum.

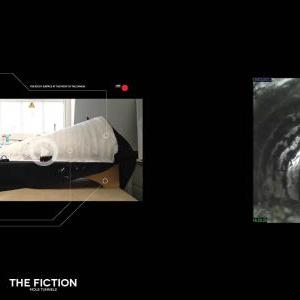

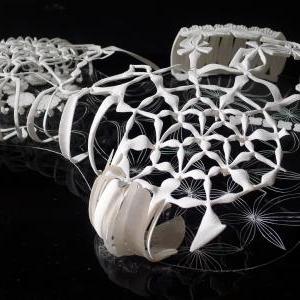

There are stories and myths surrounding the temple of the Yaskomo, the shaman of the Wai-wai people. It’s difficult to discern where the fiction ends and the reality begins, but gradually we take it upon ourselves to prototype that metaphysical state that occurs between the physical space and its inhabitation, both past and current.

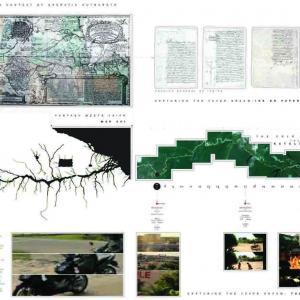

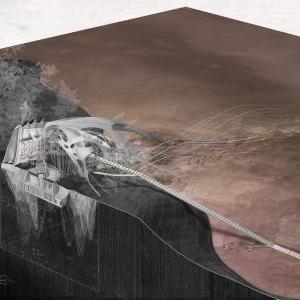

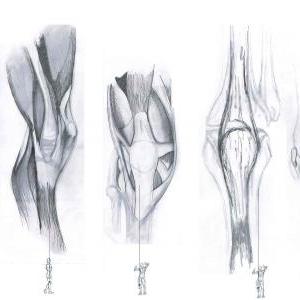

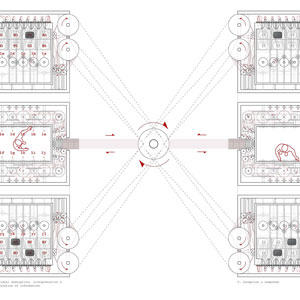

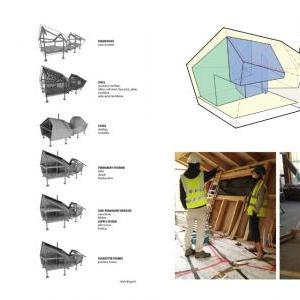

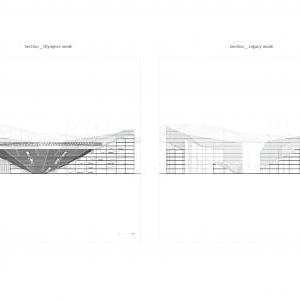

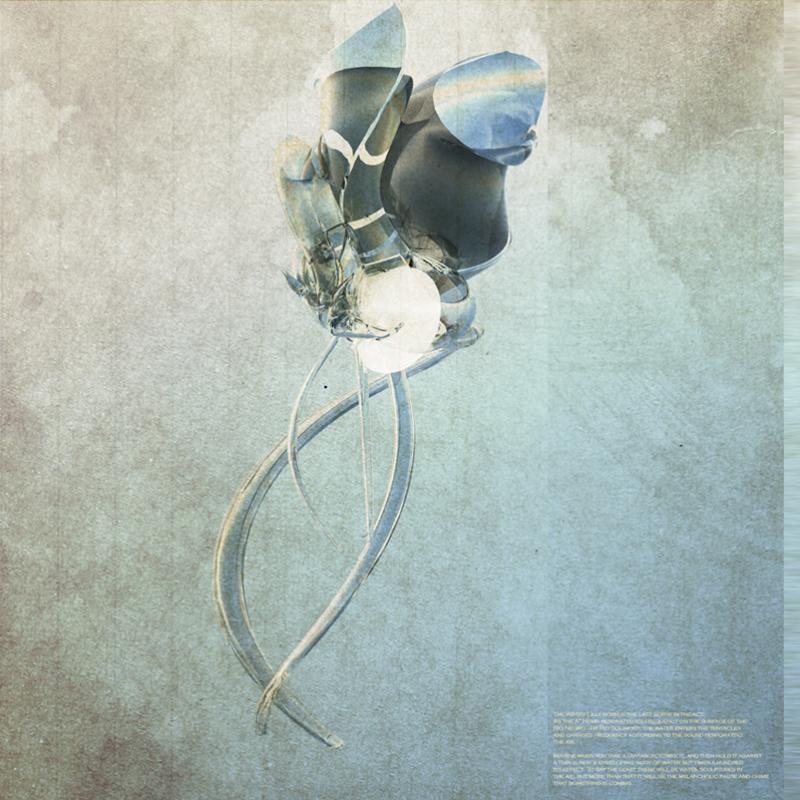

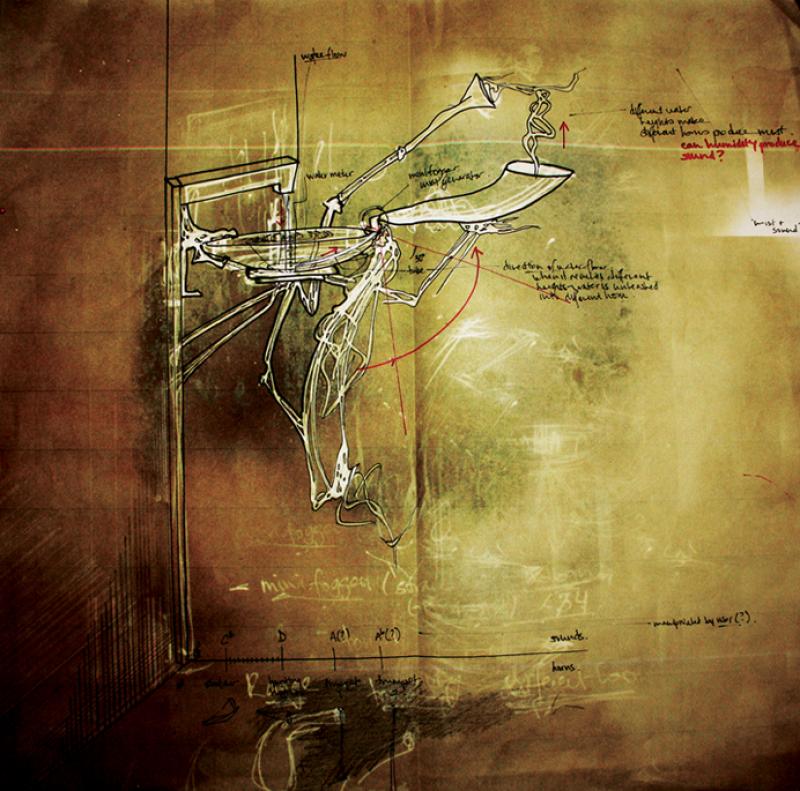

The operation of the structure is relatively simple, at least from this recovered diary that speaks of its past. It utilized a hydraulophonic principle; the same way air is used in a woodwind instrument, water is used in a central obelisk, operating an instrument based on river flow and rain levels.

Manatees and other animals local to the region such as the boto dolphins, would travel the rivers with the same mechanism embedded into their bodies; creating melodies based on the height of the river where they would find themselves.

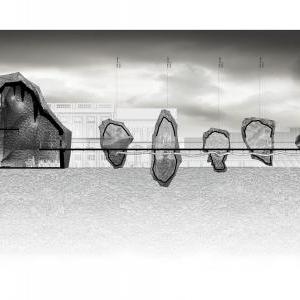

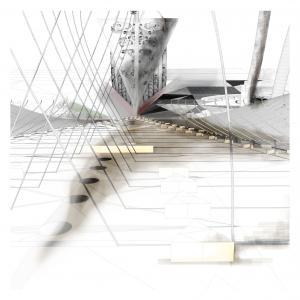

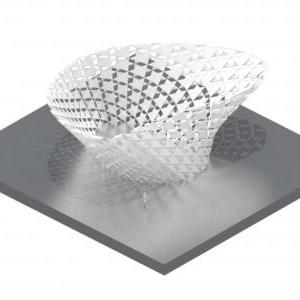

My task thus lies in re-contextualizing the fluvial soundscape in our present day, in fabricating the biomechanical relationship between the human and the machine, reconciling the divide between the inanimate and the animate in the form of a totem and its accompanying ritual, an object and its outdated program.

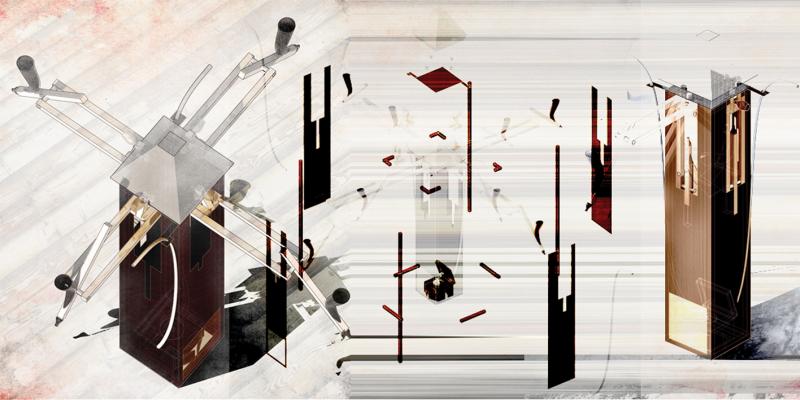

Initial prototypes investigate the pure form of the horn, and the way its presence articulates the role of the user. Is it there to be blown, or is it there to be heard? What role does the shaman have today, and can we kill the idea of the user? The shaman would blow his horn, he would chant, and he would impose a hierarchy onto the ritual of soul flight. This is now outdated, abolished when the Wai-Wai tribe was converted to Christianity in the 1950’s along with the need of the Yaskomo shaman.

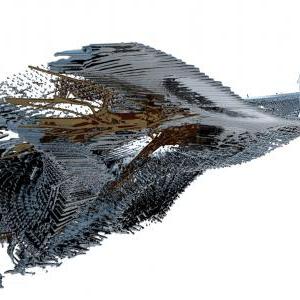

The totem hence is not a monument of the past but of what is to come. It is a speculation, which embraces the imagined fallibility of the machine, and objectives the Amazonian myth. The shaman has become the object, and the ritual now consists of a performative architecture that occurs once a year. The people along the Rio Negro must construct the totem once a year, and then burn it at the peak of the flood season. Its materiality embodies the fabric of textures scattered across the Amazon region, the decay and death that the river brings, along with the hope that new life will come as well.