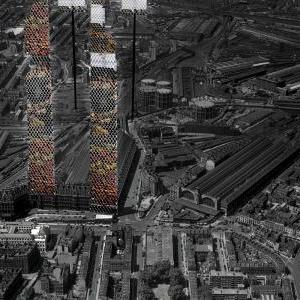

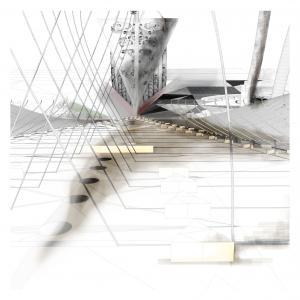

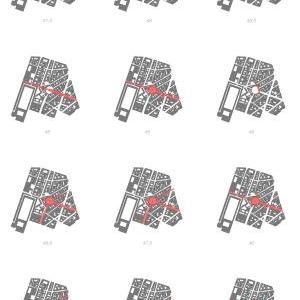

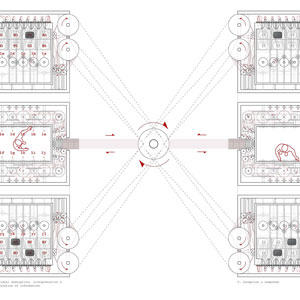

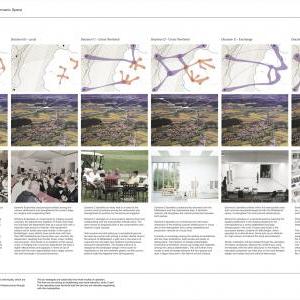

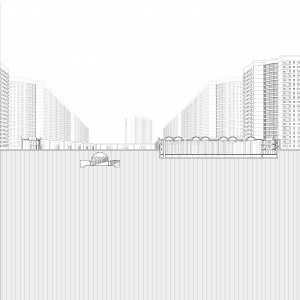

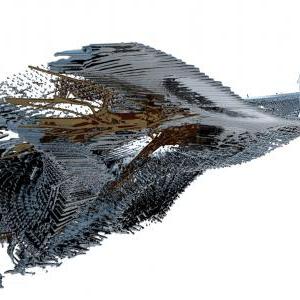

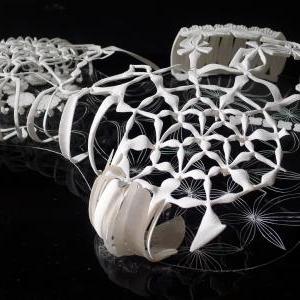

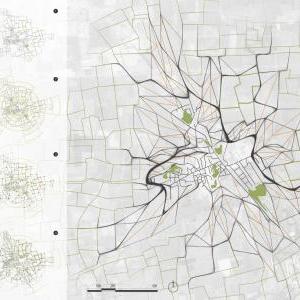

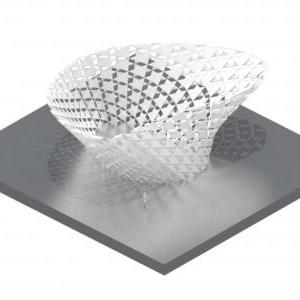

Intermediate 2 began the year by studying systematic archaeological methods of surveying a site. We travelled to a Bronze Age site in Cornwall with two archaeologist-consultants, Guy Hunt and Stuart Eve of L-P Archaeology. We learned how to measure objects of irregular shape, how to guess distances and how to reconstruct a world from its fragments. We then applied this method to our London site – King’s Cross – and built a 2m2 wood/metal model that recorded aspects of its past, present and potential future.

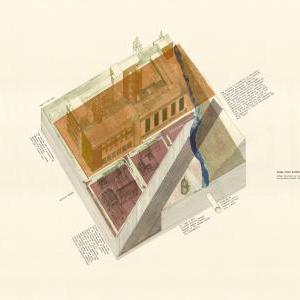

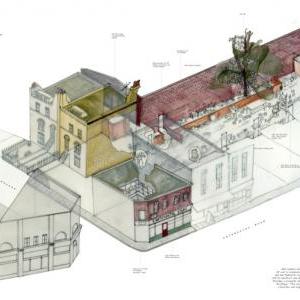

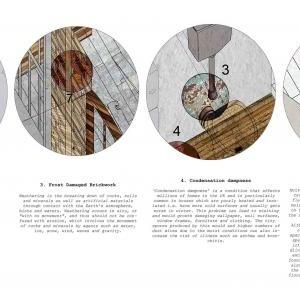

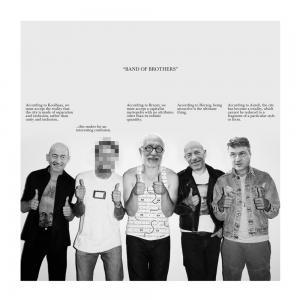

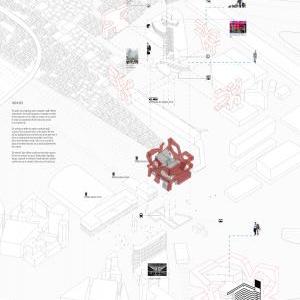

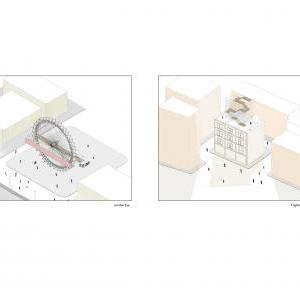

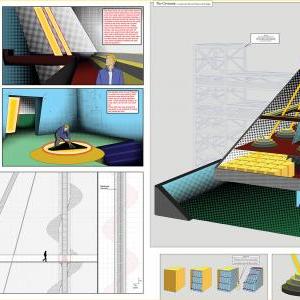

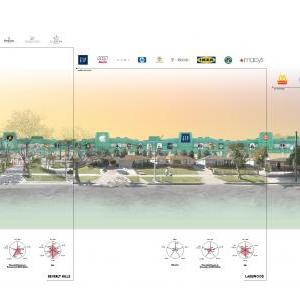

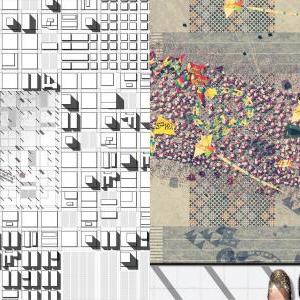

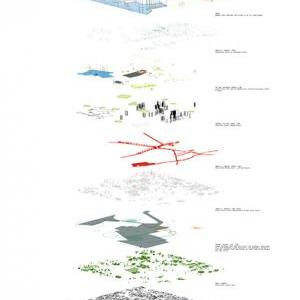

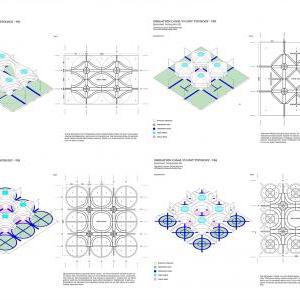

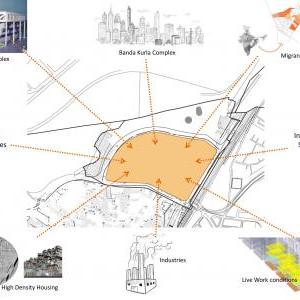

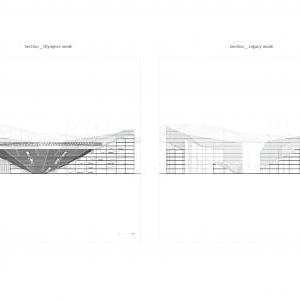

The unit then focused on a more specific site in King’s Cross: The Calthorpe – a community centre and garden that requires renovation in order to become self-sustainable in a moment of financial crisis. We used our archaeological findings to search for alternative futures for the Calthorpe project, and the solutions we found were varied. Some took a historical stance and proposed to rebuild old structures and scenography; some sought an activist approach and suggested clandestine occupations for the site; some attempted a radically pragmatic position and devised ways of maximising the use of the land; some proposed imaginative landscapes that projected future archaeologies.

In each proposal is the awareness that the past, present and future exist in continuity; that the process of architecture is cumulative, conglomerate and additive – as is (or should be) the process of living; that the material world is impregnated with meaning; that architectural interventions can be subtle, yet heroic.

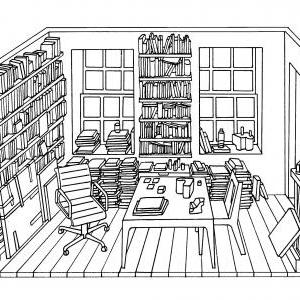

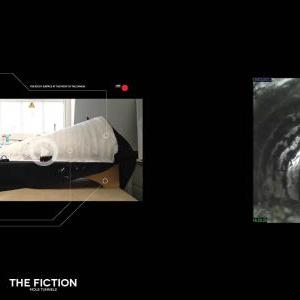

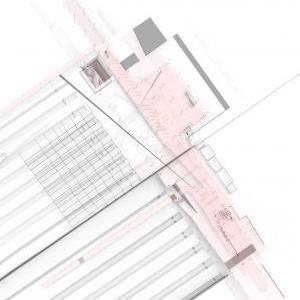

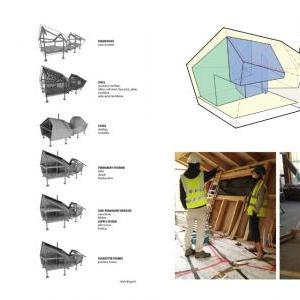

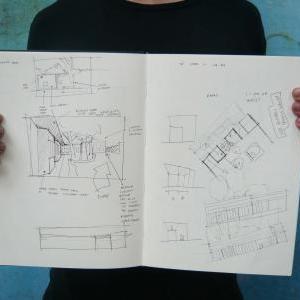

By being faithful to the guiding archae-ological principles, we employed a language that encodes materiality and events (past, present, future), which includes text, hand drawings, relief prints, animations, films, models, material samples and prototypes. We avoided visual simulations, whose freezing of time in a singular, ideal moment is so common in architecture today (ie, the building is new, the sun is shining, the users are happy). We opted instead for a language that embraces imprecision, errors, change, movement, chance and accident – in sum, an architectural language that communicates the irregularities of life.

Staff

Takero Shimazaki

Ana Araujo

Acknowledgements

Miraj Ahmed

Iphgenia Baal

Simone Brewster

Axel Bruchhäuser (TECTA, Germany)

Willem de Bruijn

Barbara-Ann Campbell-Lange

Mark Campbell

Javier Castañón

Nerma Cridge

Max Dewdney

Stewart Dodd

Francesco Draisci

Christian Drescher (TECTA, Germany)

Stuart Eve

Sarah Entwistle

Jerome Flinders

Kenneth Fraser

Jennifer Frewen

Samantha Hardingham

Jack Harrison (The Calthorpe Project)

Guy Hunt

Nannette Jackowski

Oliver Klimpel

Robert Loader

Christopher Matthews

Catalina Mejia

Annika Miller-Jones (The Calthorpe Project)

Ricardo de Ostos

Christopher Pierce

Charles Rice

Natasha Sandmeier

Brett Steele

Polly Turton (The Calthorpe Project)

Carlos Villanueva Brandt

Special thanks

Marilyn Dyer

Belinda Flaherty

Kirstie Little

Sanaa Vohra

Intermediate 2 began the year by studying systematic archaeological methods of surveying a site. We travelled to a Bronze Age site in Cornwall with two archaeologist-consultants, Guy Hunt and Stuart Eve of L-P Archaeology. We learned how to measure objects of irregular shape, how to guess distances and how to reconstruct a world from its fragments. We then applied this method to our London site – King’s Cross – and built a 2m2 wood/metal model that recorded aspects of its past, present and potential future.

The unit then focused on a more specific site in King’s Cross: The Calthorpe – a community centre and garden that requires renovation in order to become self-sustainable in a moment of financial crisis. We used our archaeological findings to search for alternative futures for the Calthorpe project, and the solutions we found were varied. Some took a historical stance and proposed to rebuild old structures and scenography; some sought an activist approach and suggested clandestine occupations for the site; some attempted a radically pragmatic position and devised ways of maximising the use of the land; some proposed imaginative landscapes that projected future archaeologies.

In each proposal is the awareness that the past, present and future exist in continuity; that the process of architecture is cumulative, conglomerate and additive – as is (or should be) the process of living; that the material world is impregnated with meaning; that architectural interventions can be subtle, yet heroic.

By being faithful to the guiding archae-ological principles, we employed a language that encodes materiality and events (past, present, future), which includes text, hand drawings, relief prints, animations, films, models, material samples and prototypes. We avoided visual simulations, whose freezing of time in a singular, ideal moment is so common in architecture today (ie, the building is new, the sun is shining, the users are happy). We opted instead for a language that embraces imprecision, errors, change, movement, chance and accident – in sum, an architectural language that communicates the irregularities of life.

Staff

Takero Shimazaki

Ana Araujo

Acknowledgements

Miraj Ahmed

Iphgenia Baal

Simone Brewster

Axel Bruchhäuser (TECTA, Germany)

Willem de Bruijn

Barbara-Ann Campbell-Lange

Mark Campbell

Javier Castañón

Nerma Cridge

Max Dewdney

Stewart Dodd

Francesco Draisci

Christian Drescher (TECTA, Germany)

Stuart Eve

Sarah Entwistle

Jerome Flinders

Kenneth Fraser

Jennifer Frewen

Samantha Hardingham

Jack Harrison (The Calthorpe Project)

Guy Hunt

Nannette Jackowski

Oliver Klimpel

Robert Loader

Christopher Matthews

Catalina Mejia

Annika Miller-Jones (The Calthorpe Project)

Ricardo de Ostos

Christopher Pierce

Charles Rice

Natasha Sandmeier

Brett Steele

Polly Turton (The Calthorpe Project)

Carlos Villanueva Brandt

Special thanks

Marilyn Dyer

Belinda Flaherty

Kirstie Little

Sanaa Vohra