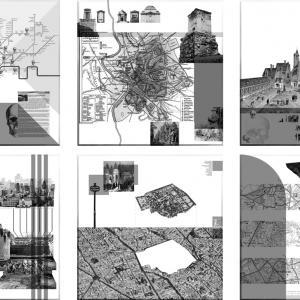

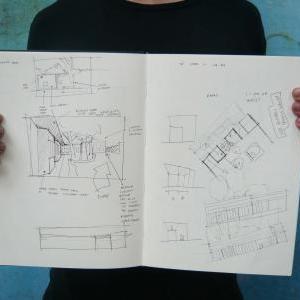

Diploma Unit 9 thrives on the looping consequences of architecture’s own stories about itself. This year the ‘ruin’ was posed as a straightforward point of entry for a brief that would explore the ruin as an artefact and the embodiment of a cultural and architectural stagnation. Like last year’s exchange of the room and the city, this year’s work on the ruin led to the making of narratives within narratives, which demanded a comprehension of time and space as utterly elastic.

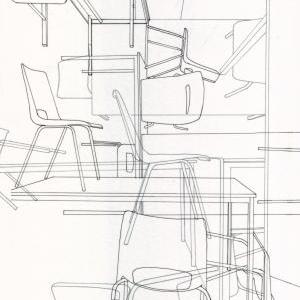

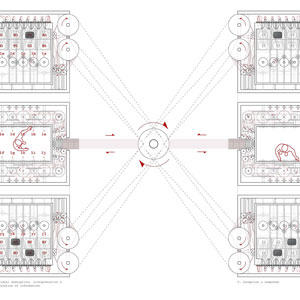

As Georges cut a series of holes through the physical spaces of the AA he confronted not only the physical exhaustion of a Georgian building, but also the discontinuities of the architectural conceit that makes up the corridor (which he demonstrated as an entity that does anything but connect).

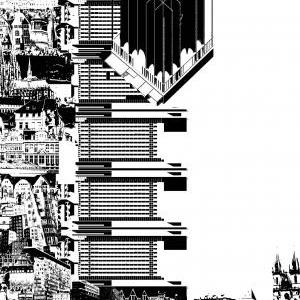

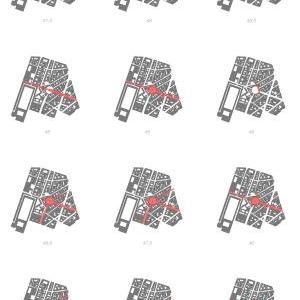

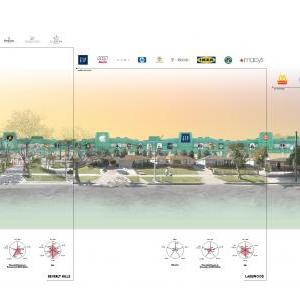

Antoine battled an identity crisis on two fronts: the future of the European city and the future of the architect (and himself) in this unknown terrain. Both Antoine and Georges destroyed in order to build; yet neither conceded a return to the tabula rasa, which reveals itself today as its own kind of architectural ruin.

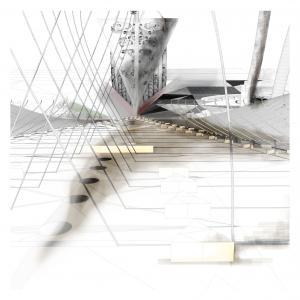

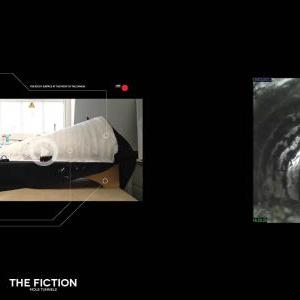

Ariadna’s project explores so many sub-narratives that we never know which story is the real one set in the place that still might be Manhattan. The project is at once a film as well as a set occupied by both buildings and their architect – a new, unexpected kind of built world. Meanwhile Eleanor battles with the axonometric, an architect’s text, and an architect who becomes, like Luke’s Darth Vader, a father she must destroy to find her place in an architectural world far, far away.

Our work on the ruin was a wipeout where cities that were once whole now stand as devastated landscapes. Through the settling dust we learned this: whatever the ruin may be, its inverse is unknowable – and within that ambiguity lies the potential for an architectural project and the possibility to locate the architect within this new context. It enables us to make work that is committed to what we do best – architecture about architecture.

Staff

Natasha Sandmeier

Special thanks to our guests and critics and support

Charles Arsène-Henry for his seminars and inspiration

Amandine Kastler

Ana Araujo

Andrew Yau

Barbara-Ann Campbell-Lange

Belinda Flaherty

Brett Steele

Christopher Pierce

Dolores Ruiz Garrido

Doreen Bernath

Evan Greenberg

Fabrizio Ballabio

Francesca Hughes

Gabriela Garcia

de Cortazar G

Inigo Minns

Javier Castañón

Kenneth Fraser

Manolis Stavrakakis

Maria Fedorchenko

Marilyn Dyer

Marina Lathouri

Mark E Breeze

Mark Campbell

Mark Cousins

Martin Jameson

Matthew Butcher

Michael Weinstock

Nacho Marti

Ricardo de Ostos

Shin Egashira

Shumon Basar

Sylvie Taher

Takero Shimazaki

Tarek Shamma

Theodore Spyropoulos

Thomas Weaver

Tyen Masten

Wing Tam

Ruin is not the end.

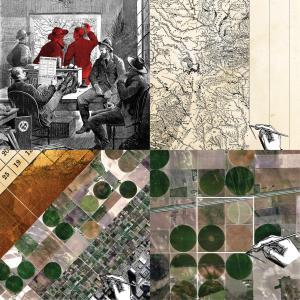

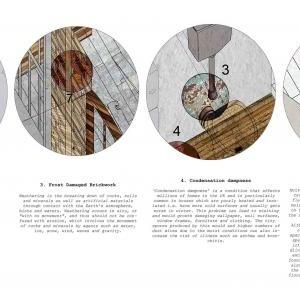

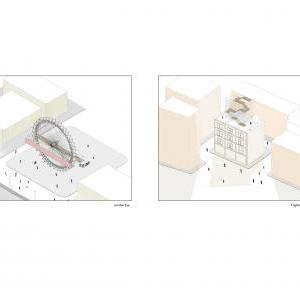

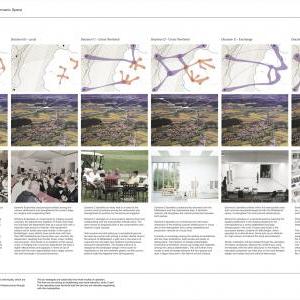

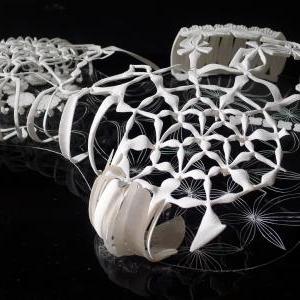

Through out the last 6 centuries, the role of ruins has transformed with our culture, referencing our civilization and our attitude toward architecture in nature.

This attitude, references our past and influences our future.

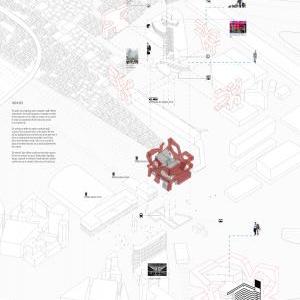

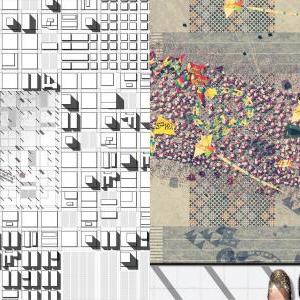

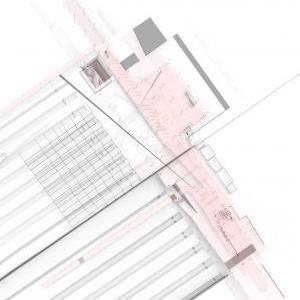

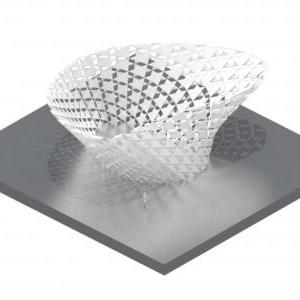

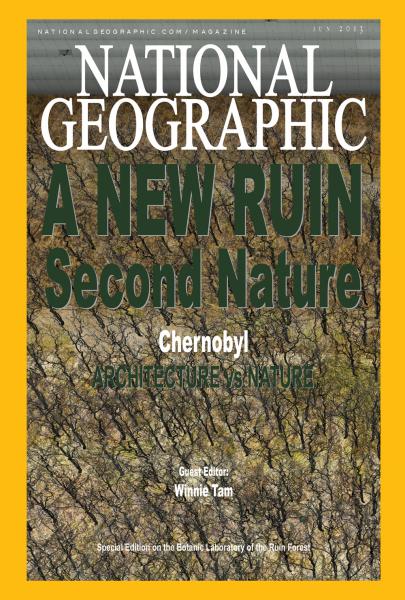

This project challenges the conventional interpretation of ruin through this month's issue of National Geographic, feature editing the Chernobyl Lab. This Lab proposes ruin’s future - the next stage of its evolution

- a ruin made new again.

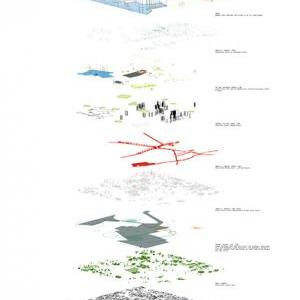

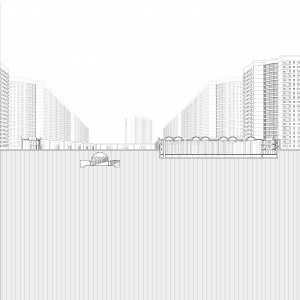

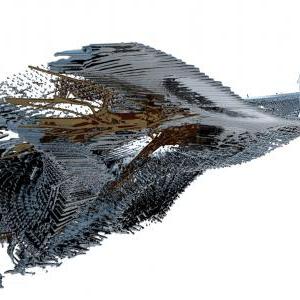

Framing the landscape of the Red Forest, Chernobyl Lab shifts the focus from architecture to nature. It visualises a new meaning of ruin, which no longer speaks about death, but rather celebrates regeneration.

Through learning and manipulating the forest’s ruin evolution, would Chernobyl Lab help to find a way for architecture to escape from the destiny of ruin?

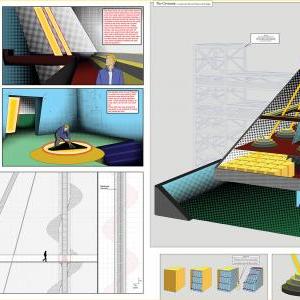

Our love on ruin is not induced only by its aesthetic, we cherish these relics because we can find our culture embedded within the way we handle and value them. Although the role of ruin changes constantly, one thing remains constant, is the fact that we always find nature in architectural ruins, revealing our close bond with the organic world and explaining our indestructible desire to tame the wilderness.

We can’t help but admire nature’s ability to always grow back, over the remnants of our own creations, leading to the conclusion that nature always prevails. Though, through the future ruin of the Chernobyl Laboratory, we understand that architecture is actually not too different from nature.

Architecture as a building, cannot escape from the limitation of its materiality, and would inevitably fall into decay; but architecture as a concept and its spirit, is just like nature: as one building decays, it encourages a new one to rise up. Architectural ruins are the inspiration for architects to carry on designing. The architects’ inability to admit defeat, which is our nature, makes architecture immortal, and also makes it possible for architecture to carry on this never ending battle against nature.