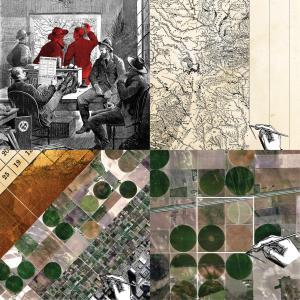

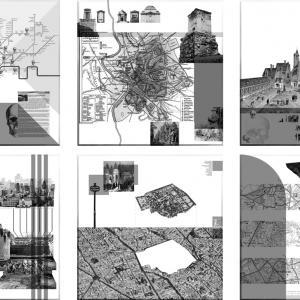

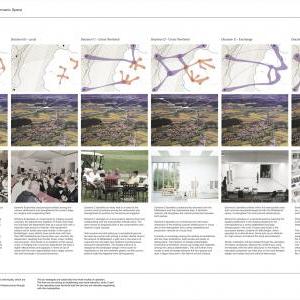

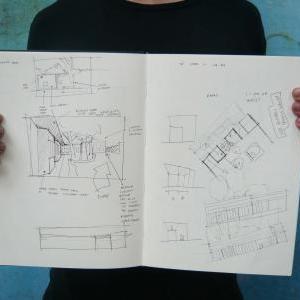

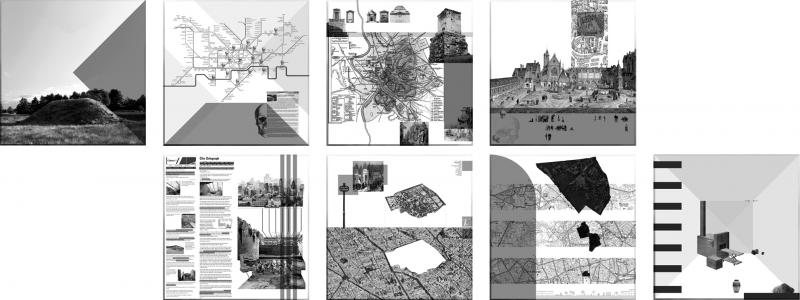

Diploma Unit 9 thrives on the looping consequences of architecture’s own stories about itself. This year the ‘ruin’ was posed as a straightforward point of entry for a brief that would explore the ruin as an artefact and the embodiment of a cultural and architectural stagnation. Like last year’s exchange of the room and the city, this year’s work on the ruin led to the making of narratives within narratives, which demanded a comprehension of time and space as utterly elastic.

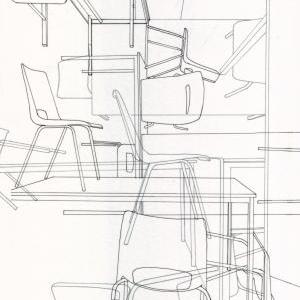

As Georges cut a series of holes through the physical spaces of the AA he confronted not only the physical exhaustion of a Georgian building, but also the discontinuities of the architectural conceit that makes up the corridor (which he demonstrated as an entity that does anything but connect).

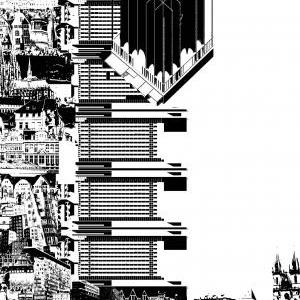

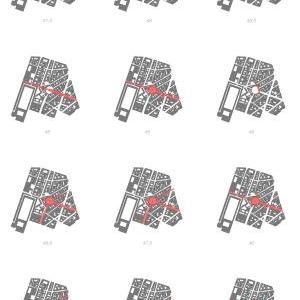

Antoine battled an identity crisis on two fronts: the future of the European city and the future of the architect (and himself) in this unknown terrain. Both Antoine and Georges destroyed in order to build; yet neither conceded a return to the tabula rasa, which reveals itself today as its own kind of architectural ruin.

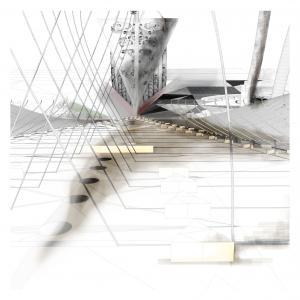

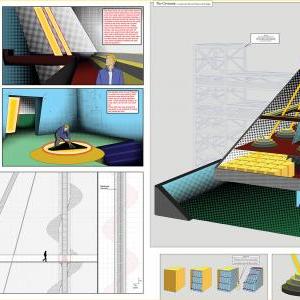

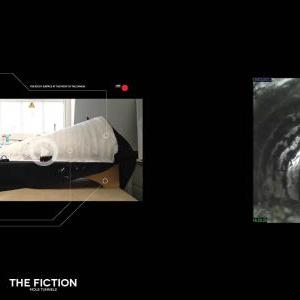

Ariadna’s project explores so many sub-narratives that we never know which story is the real one set in the place that still might be Manhattan. The project is at once a film as well as a set occupied by both buildings and their architect – a new, unexpected kind of built world. Meanwhile Eleanor battles with the axonometric, an architect’s text, and an architect who becomes, like Luke’s Darth Vader, a father she must destroy to find her place in an architectural world far, far away.

Our work on the ruin was a wipeout where cities that were once whole now stand as devastated landscapes. Through the settling dust we learned this: whatever the ruin may be, its inverse is unknowable – and within that ambiguity lies the potential for an architectural project and the possibility to locate the architect within this new context. It enables us to make work that is committed to what we do best – architecture about architecture.

Staff

Natasha Sandmeier

Special thanks to our guests and critics and support

Charles Arsène-Henry for his seminars and inspiration

Amandine Kastler

Ana Araujo

Andrew Yau

Barbara-Ann Campbell-Lange

Belinda Flaherty

Brett Steele

Christopher Pierce

Dolores Ruiz Garrido

Doreen Bernath

Evan Greenberg

Fabrizio Ballabio

Francesca Hughes

Gabriela Garcia

de Cortazar G

Inigo Minns

Javier Castañón

Kenneth Fraser

Manolis Stavrakakis

Maria Fedorchenko

Marilyn Dyer

Marina Lathouri

Mark E Breeze

Mark Campbell

Mark Cousins

Martin Jameson

Matthew Butcher

Michael Weinstock

Nacho Marti

Ricardo de Ostos

Shin Egashira

Shumon Basar

Sylvie Taher

Takero Shimazaki

Tarek Shamma

Theodore Spyropoulos

Thomas Weaver

Tyen Masten

Manon Mollard

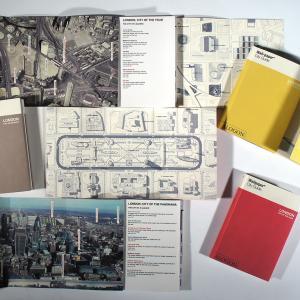

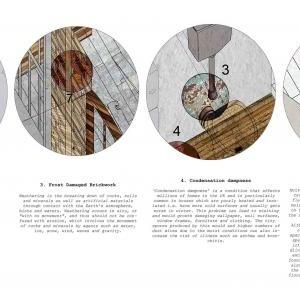

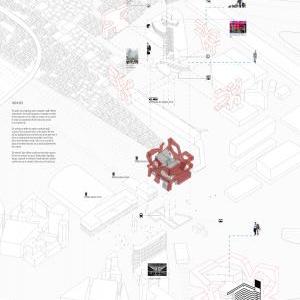

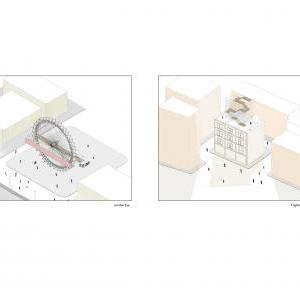

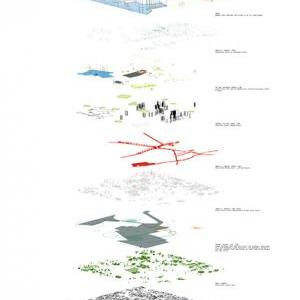

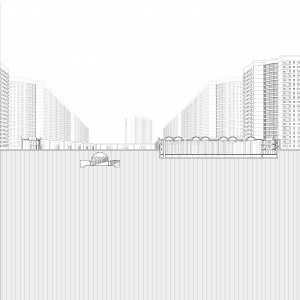

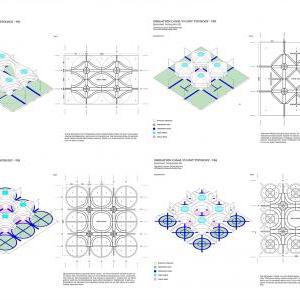

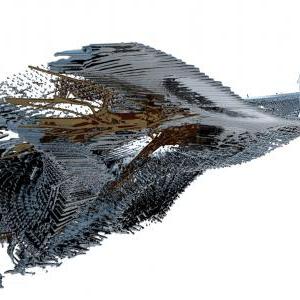

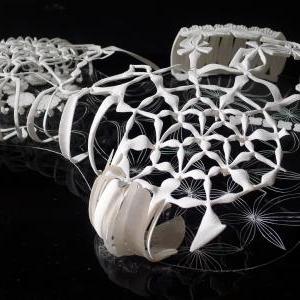

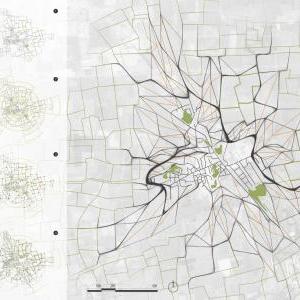

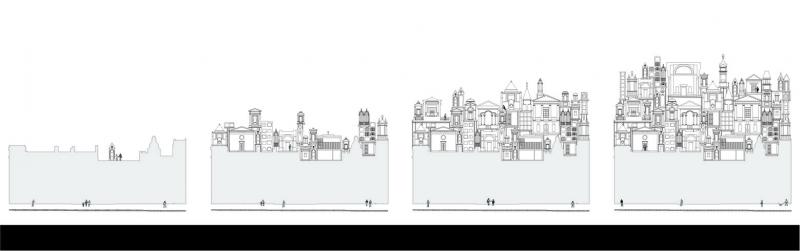

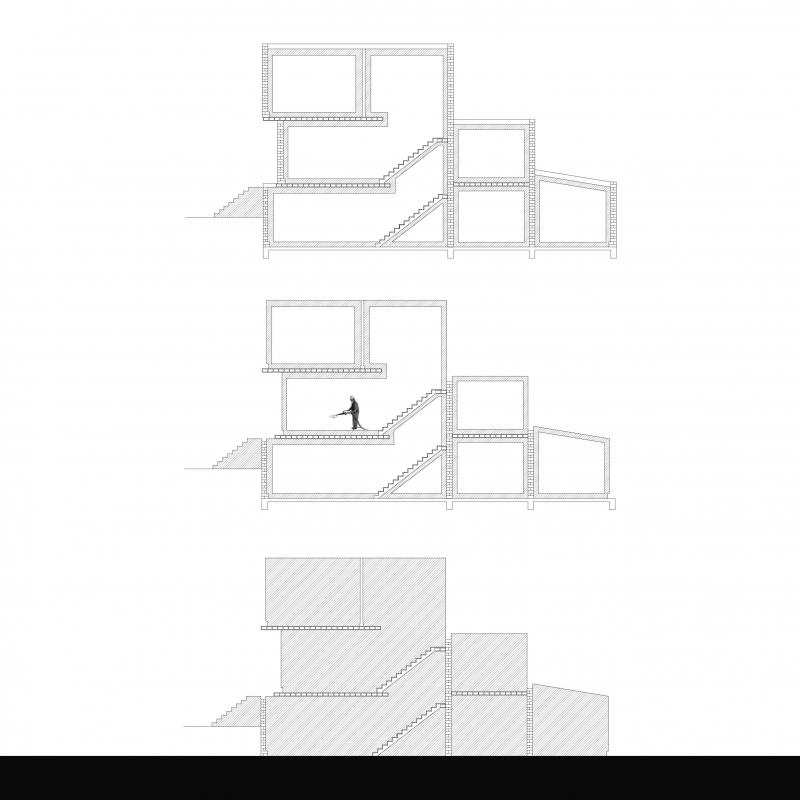

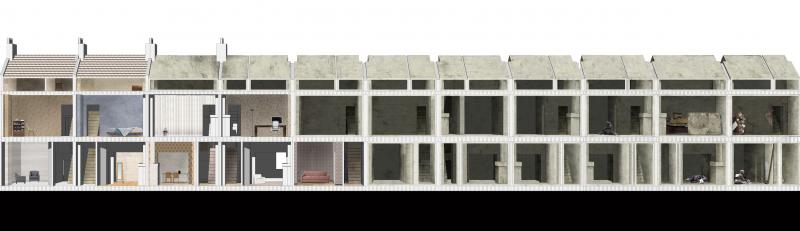

THE CITY THAT NEVER DIES seeks to reclaim a space for the dead within the modern metropolis, redefining the shape of inhabitable ground in the city, between the world of the living and that of the dead, making London endless.

It is not only our views on death that are affected but the experience of our urban environment that is modified. The city regains a strong connection to its memory and consciousness, and the strange mirroring effect between the two worlds blends them into a single entity.

Architecture mirrors the process of mortality and the new inhabitable ground finds its way in this interweaving of the London of the living, the London of the dead, and the dead London. The city never dies but lives in the constant awareness of it..